Published 2026-01-19

Imagine this scenario: You have an automated production line that has been running for many years, or a reliable robotic arm system. It has been stable, doing repetitive work every day. Until one day, you need to add a new function to it - such as letting the end effector complete an additional detection action, or letting the rhythm of the entire production line adjust in real time according to the order.

You open the control cabinet, face the bundles of intertwined cables and layers of codes, and suddenly feel a headache. If you make one change, you are afraid of affecting the overall situation; if you don't upgrade, the business will continue to rush you. Is this familiar feeling a bit like when you face those huge, old software systems that affect your whole body?

In the world of software architecture, people often refer to a system that packages all functions together and is tightly coupled as a "monolithic architecture." It's like a large cast metal component - solid and complete, but once a part needs to be changed, the entire thing may have to be recast.

What are the characteristics of such a system? Early development is fast and deployment is simple, like a freshly assembled servo system with all components in a box and clear wiring. But as more and more functions are added, this "box" becomes extremely large. To update a module, you need to test the entire system; want to rewrite a small function in a new programming language or tool? Almost impossible because everything is so tangled together.

The more practical problem is: when this behemoth needs to be expanded, you can only expand it as a whole. Just like in order to increase the speed of a certain station in a production line, you have to replace all the motors in the entire line with more powerful ones - the cost is high, but the efficiency improvement is limited.

So, someone put forward the idea of "microservices". This concept is not new. The logic behind it is the same as when we deal with complex mechanical systems: break down large problems into small modules, let each module work independently, and then collaborate with them through standard interfaces.

For example, in an intelligent warehouse robot system, you may have:

Each service can be developed, deployed, scaled, and even restarted independently without bringing the entire system down. Want to upgrade your positioning? Just update the servo control service. Is the traffic suddenly focused on warehousing queries? Just add resources to the data service separately.

Does this sound closer to the intuition of our mechanical systems? Wherever there is a bottleneck, that's where it is; whichever module technology lags behind, that one is replaced without having to start over.

Of course not. It brings freedom but also introduces new complexity.

Splitting a monolith into microservices is like transforming an integrated device into a modular workstation. You gain flexibility, but you also need to consider:

Microservices require a set of automated "operation and maintenance infrastructure" - tools for service discovery, load balancing, and monitoring and alarming. This is equivalent to equipping your modular production line with an intelligent central control scheduling system. Without these, microservices may be more difficult to manage than monoliths.

If you are starting a new, small project with clear boundaries, a monolithic architecture may get you online faster. Just like designing a small dedicated device for a simple action, the all-in-one version is more economical and reliable.

But if you are facing an already large system that needs to continue to evolve rapidly—such as a manufacturing unit that is being upgraded from automation to intelligence, or a management and control platform that needs to connect to more and more external interfaces—planning to evolve to microservices is likely to be a wise choice to avoid the "pain of reconstruction" in the future.

“Planning” here is important. You don’t have to chop the boulder into pieces overnight. You can start pilot projects from modules with relatively clear boundaries and frequent changes, and gradually accumulate experience. Just like renovating a production line, first make a certain station independent into a module, and then move forward to the next one after the operation is stable.

existkpower, we often face similar challenges from our customers in mechanical system integration. A common misunderstanding is: over-integration. The motor, drive, controller, and sensors are all bundled into a black box that cannot be disassembled. Initial debugging seems convenient, but later maintenance, upgrade, and replacement costs become extremely high.

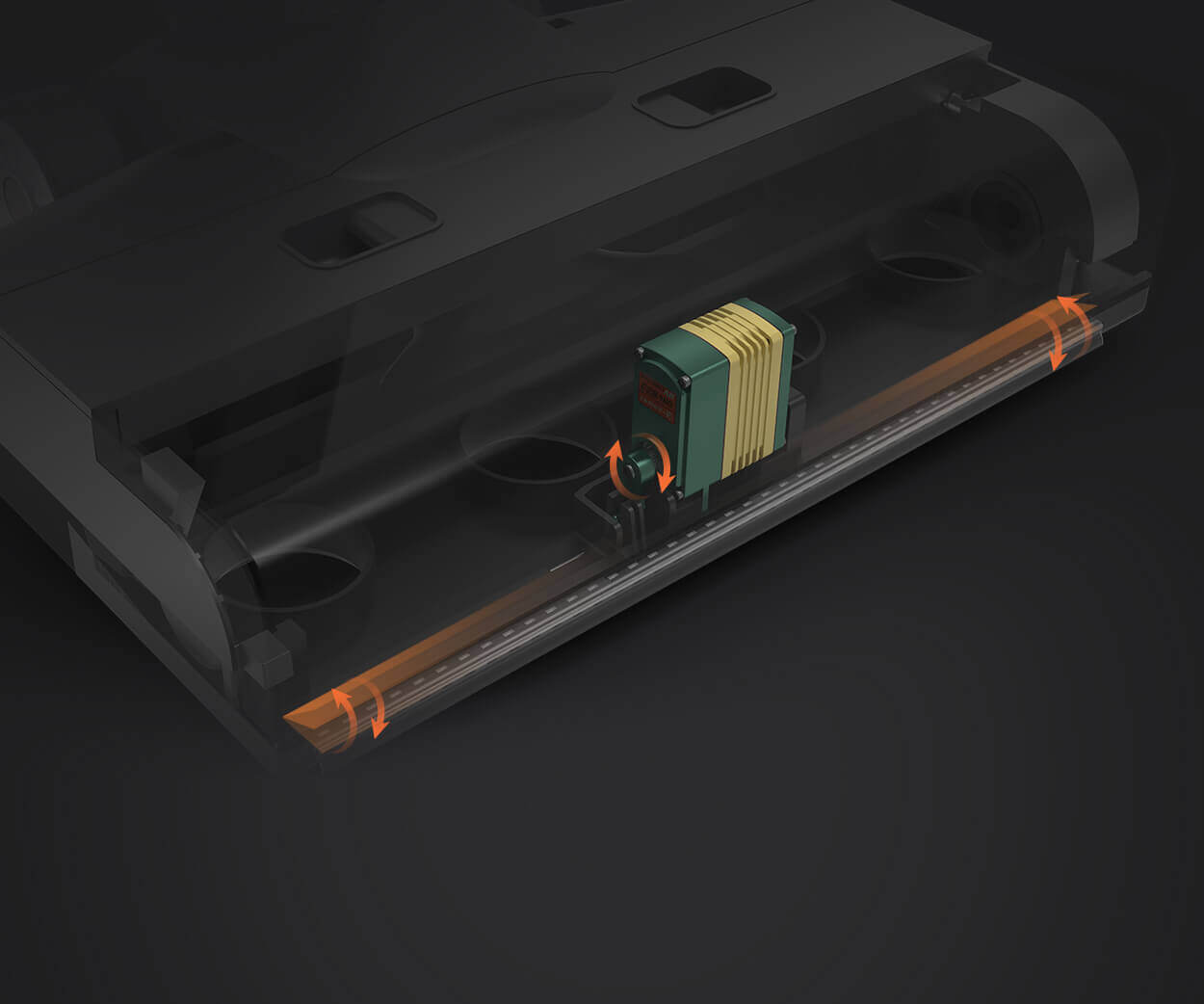

A good design will leave clear physical and electrical interfaces. If the servo motor is broken, it can be quickly disassembled and replaced; if the control accuracy needs to be upgraded, the driver can be updated independently. Modules talk to each other through standard protocols rather than welded internal logic.

Isn’t this the case with the design of software architecture? What should be pursued should not be the fashion of the technology itself, but the long-term maintainability, scalability, and ability of the system to cope with changes. Reliable systems, whether soft or hard, should be "robust" rather than "rigid".

The next time you are faced with that old system that is causing you a dull pain, or when you start to design a new platform that will carry your business for many years to come, you might as well jump out of the code details and think like a system architect:

The answers to these questions will naturally guide you to make more appropriate choices. Architecture is not absolutely good or bad, only whether it is suitable for you now and for you in the near future.

After all, the best system is not the one that uses the most dazzling technical framework, but the one that can evolve smoothly at the minimum cost when changes are needed. This is essentially the same as the maintainability and upgradeability we pursue in the mechanical field - both are to create more reliable and flexible value in a longer life cycle.

Established in 2005,kpowerhas been dedicated to a professional compact motion unit manufacturer, headquartered in Dongguan, Guangdong Province, China. Leveraging innovations in modular drive technology,kpowerintegrates high-performance motors, precision reducers, and multi-protocol control systems to provide efficient and customized smart drive system solutions. Kpower has delivered professional drive system solutions to over 500 enterprise clients globally with products covering various fields such as Smart Home Systems, Automatic Electronics, Robotics, Precision Agriculture, Drones, and Industrial Automation.

Update Time:2026-01-19

Contact Kpower's product specialist to recommend suitable motor or gearbox for your product.